HOW I EMIGRATED TO AMERICA, THE LAND OF MY BIRTH

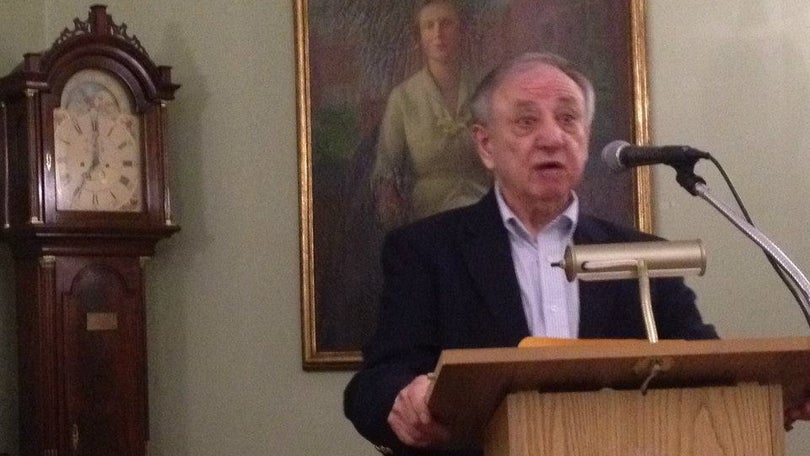

George Monteiro

When I was eight months old I was sent into exile. Let me explain. It all begins, naturally, with family. We always had my Mother’s birthday cake on the twenty-ninth of November, which should not have been a problem, except that she kept insisting, every year, that her real day of birth was the eleventh or twelfth. It always puzzled me, this not knowing your birth date for sure. Every year on the twenty-ninth, there would be cards, the small cake and the candles, and always her gracious "yes, thank you, thank you. It’s a nice cake. But you know, I think my birthday is really in early November, on the eleventh, the twelfth maybe."

I could never figure that one out. Why didn’t she know for sure? And of course she wouldn’t think of celebrating her birthday on the eleventh or twelfth even if we tried to do it. Then one day I got an answer. It all started when she told me the story of the woman in Taunton we had just visited on Saturday. The woman had been injured in a car accident and was still recovering from her injuries.

"That woman was amazing. She worked miracles. It wasn’t her fault they found out about me and Lucinda." She talked while she sewed, as she always did, not wanting, I suppose, to waste the time doing only one thing. "That was the doing of some of the old-timers who wanted to get in good with the authorities. You know who they are, the Pireses and the Cardanhas. But it’s best to forget them, at least forget about what they did to us. Still, that woman—it’s sad to see her now. She doesn’t look powerful. Life’s been tough on her, at least lately. But maybe after she gets healthy again, gets a bit stronger, she’ll be all right. But she will never be her old self again."

In my mind’s eye I saw this woman again, saw her as she was now—fiftyish, wrapped in a faded gray-green flannel bathrobe, her pepper-and-salt hair cut short like a man’s, wearing a plain square watch with a large face set in a heavy black leather strap, the face showing out from the inside of her wrist. "Look, look at these," she bossed, holding out some newspaper clippings. "Notice the picture of the accident. Good thing that photographer came along. See how that guy’s car is rammed up against the side of my car, the car I was riding in, I mean. Somebody’s got to pay for all this, my injuries, my disability, my loss of working time. I’ve got a good lawyer. I couldn’t use Andrade, of course. He’s family—well as good as family—and it might hurt the case. Besides, I’ve got an excellent lawyer. I’ll win this one. You’ll see. Everybody will see. I’ll win it. I’ll do it."

She put the clippings down, on top of the desk, stood up straight, thumped her fist into her open hand, twice, three times, and then again leaned down to the desk, picked up the clippings, glanced at them, put them back, in a drawer this time, and pushed the drawer flush. "If I could get those boys out of the trenches, and I did get them out, I certainly did, I can win this case."

"That woman was remarkable, what she did nobody could do," said my mother, without missing a stitch, then drawing in her breath and talking to the end of her story. "That’s why you were with me back in Portugal on your first birthday, that’s why you took your very first steps in Freixo-de-Espada-à-Cinta where your father is from. That’s why the first word you ever said, you said in Vila Ruiva da Serra. Remember that picture I keep with the other pictures in the drawer? You’re walking along in the Lameiro and you’re hanging on tightly to a bottle? A small brown bottle full of milk? Remember?

"What she did in the War was miraculous. One miracle after another. She pulled boys right out of the trenches in France, right out of the fighting. She got them away from the bullets, from the shells, away from the gas. How did she do it? She proved that those boys had been born in America. They were Americans who didn’t belong in any foreign army. That’s the way it started. But after a while things changed, and the truth was that some of the later ones that she got out of France weren’t American-born at all. Some of them were children born to immigrants who had been in America all right, but they were born only after the parents had returned to Portugal. No, these boys were Portuguese all the way, and before they were sent to the War they hadn’t even been away from their villages, let alone out of the country. How did she do it? It so happened that these boys had names similar or identical to names of other boys their age who had been born to Portuguese parents in the United States, taken back to the old country, and had the misfortune, poor things, to die in childhood. Working from the United States, that woman dug up all the papers, birth certificates and what have you, belonging to the now-dead children so that they could be used for the grown-up boys now in France. It was not an honest thing to do, of course, but it worked. And nobody was hurt by what she did.

"Now let me tell you why we—you and I—were in Portugal, marking time just six months after you were born, born right here in America, in this very house." She paused, having come to the end of that particular bit of mending, on a boy’s white shirt, and bit off the thread. She folded the shirt and put it aside, and then picked up one of her own blouses, looked it over carefully, sighed, and began to sew up a tear at the sleeve, just above the cuff.

"When the War was over," she resumed her story, "that woman went back to doing whatever it was she did in peacetime. But a few years later, when they stopping allowing immigrants to come into America, she had another good idea. She decided that she knew a way to bring over young men and women. She would arrange it so that they could present themselves at the American Consulate in Lisbon as Americans and thereby escape the immigration laws. These men and women would be taught to assume new names, the names written on the American passports she finagled for them. And in that way she got them to the United States. A few of them kept right on with the new names, but for the most part these new Americans were too well-known to those immigrants who had come before them to stick to the names on their passports. Besides, some of them went by nicknames anyway. So they never used their assumed names. That was the way it was with me and Lucinda.

"She was able to do all this, and she did it for a long time, maybe three or four years. My father—your grandfather—was living in the United States by himself just about the time she was sneaking people into the country. He heard about it. People weren’t supposed to talk about it, but it was an open secret. He never forgot it, and when, later, he was back in Vila Ruiva da Serra, this time for good, and he took a hard look at what his daughters were facing by way of a future, he remembered this woman who worked miracles for others. Why not for him, too, or at least for his daughters. It was not yet time to think about the youngest one, but he had two nearly grown daughters and their prospects, as far as he could tell, were so bad he had to do something for them. Naturally his thoughts ran to the woman in America who could arrange it so that they wouldn’t have to spend the rest of their lives in that God forsaken village. Things those days were awful, really bad, and they were not much better in the rest of the country. Thank God his son was already in America. Maybe he could get that woman to agree to work on his daughters’ behalf. Maybe. ‘Please take them out of this miserable place,’ he begged the woman. He had sought her out immediately when he heard that she was visiting relatives in Melo. ‘I want them to go to America. When they get there they can live with their brother. You know him. He’s your friend Grace’s brother-in-law. We’re practically family, you see. Aren’t we? You’d be doing something for the family, and you’d be doing it—charity—for these girls, for me and my wife—in the sacred memory of your father and mother.’ Fortunately, he told her, he could also scrape up the money to get his daughters to Lisbon, right to the ship. The passage-money itself, he assured her, would come on a loan from his son, your uncle—Tio Temudo.

"In time we received ‘our’ passports. They were issued in names different from ours, of course, and they showed birth dates that were not ours either. It all went well. In less than a year, Lucinda and I were here, in America, living with your uncle and working in the Tamarack mills. The Tamarack closed down a long time ago, but when we started working there it was full of people like us, people of all nationalities. Hundreds, maybe thousands. That’s where I met your father. He was a strong man, handsome, serious, healthy. He was older than I was, more mature. He had lost his wife many years earlier. She was only nineteen when she died, and she left him with a small son to raise by himself. The boy wasn’t three years old. She died of something called a milk leg. For the next ten years he raised his son alone. Your father was thirteen or fourteen years older than I. We got married, and a couple of years later you came along. It was right after that it happened. Somebody turned me in to the Feds—me and your Aunt Lucinda. But before they could come for us, we got a tip they knew everything, that we were here illegally, and so on. Your aunt immediately skipped the country. She made a beeline right to Vila Ruiva da Serra, vowing she’d never leave home again no matter what. As far as she was concerned, she had never set foot in America. But what could I do, married and with a brand-new baby? Your father and I talked about it. We agonized. Finally, it was decided that I had to turn myself in to the immigration officials. Good thing we did. They treated us fairly, your father and me. We were told that I had to leave the country for at least a year, and that if I did so I would then be allowed to come back—legally this time—as your father’s wife and as the mother of an American child. They suggested that I go to Mexico or Canada, because they were the foreign countries closest to America. But your father decided against them. Rather than Mexico or Canada, we should go home. ‘After all,’ he explained, ‘ you can stay mainly with your family, and part of the time you can stay with my family, my father and mother, my brother and his wife. They can all get to know you. On both sides of the family, they’ll have an opportunity to see the baby. That way time will go faster for you, and knowing you are safe with my family and your family, it will go faster for me, too.’

"And that’s what happened. The sea voyage, though, was very long and the weather was bad. It was very crowded below deck. I thought we’d never get there." She hesitated, and then said, "I just remembered something funny. When we finally arrived in Lisbon—no, I mean Providence—and were told to line up to prepare for disembarking, we ended up way back in the line, an endless line that didn’t seem to be moving at all. I was carrying you in my arms, of course, and you were getting heavier by the minute. But you were being good, just looking around, quietly, at everything in sight. You were perfectly happy, minding your business, until, that is, I pinched you—hard—and you began to bawl, first, and then to scream at the top of your lungs. It got everybody’s attention, of course, and we were promptly called up to the front of the line. They went through my papers as quickly as they could. In two minutes we were out of there and on our way down the gangplank. You weren’t much of a crier usually, but you were still sobbing when we set foot on the dock, where your father was waiting, smoking a cigarette—which didn’t bother me a bit."

Note: Dr. George Monteiro, Professor Emeritus of English and Portuguese at Brown University