“The Horta Swell,” by Victor Rui Dores

Translated by Katharine F. Baker

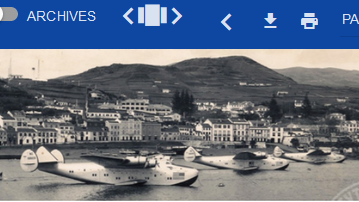

World War II was breaking out, and in the Azores a small city exuding an air of cosmopolitanness was awakening to one of the most golden periods in its history – the Horta that between 1939 and 1945 would receive in its bay the moorings of regular flights of the Boeing 314, commonly known as the Pan American Airways Clipper, ferrying passengers between the United States of America and Europe.

During those years, clippers tied up in Horta Bay 656 times, transporting 9,729 passengers in transit as well as 986 who disembarked and 1,931 who boarded. These figures are quite considerable at a time when travel on seaplanes was available to but a few. Just remember that the price of a ticket to cross the Atlantic was $375 (a small fortune then).

The Pan American clippers, those “Transatlantic ships of the air,” brought renowned people to Horta. Industrialists, merchants, millionaires, princes and aristocrats landed here. And a whole gallery of movie stars, including the divine Greta Garbo, Charles Boyer and Tyrone Power (the latter two setting the city’s female hearts aflutter), Lilian Harvey, Carole Landis and Kay Francis, among others. Also famous politicians like, inter alii, future U.S. President Truman; Clement Attlee, who would become British Prime Minister; Lord Halifax, then the United Kingdom’s ambassador to Washington, closely associated with Winston Churchill; and Joseph Kennedy, Sr., who in 1939 was U.S. ambassador to the U.K.

Also passing through the “Horta airport” (as this city’s bay was called) were figures from European royalty such as heir to the Austrian throne Otto von Habsburg, and Lady Mountbatten, married to an uncle of the current Duke of Edinburgh. Another illustrious passenger in transit was Pedro Domecq, an Andalusian nobleman whose name was linked to the famous cognac, accompanied by Countess Hertha von Gradenigo.

It was a period of prosperity for Horta’s merchants as well as for the Hotel Pan-American and local cafés, restaurants and clubs, which were always jampacked since, in addition to the customer turnover generated by the clippers, Horta was a base for refueling, repair and R&R for Britain’s Royal Navy and the merchant marine cargo ships crossing the Atlantic. In addition, the city had already become a meeting place for cultures, because the English and German, and to a lesser extent the French and Italian, employees of the submarine telegraph cable companies had been stationed there since the late 19th century. Horta was at the time a kind of transatlantic Casablanca. For further background, see Carlos Guilherme Riley’s study “The Horta Swell,” Crónica de um Natal Transatlântico, 1939 D.C. [The Horta Swell, the Chronicle of a 1939 A.D. Transatlantic Christmas] (Horta: Núcleo Cultural da Horta, 2016).

Some of the clippers’ stopovers were etched in the collective memory of Faialenses. That was the case with a remarkable event I shall now recount. In its December 26, 1939, issue, O Telégrafo reported that “due to bad weather in the Atlantic, Pan American’s Atlantic Clipper and Dixie Clipper did not leave the Horta airport for North America as scheduled last Saturday afternoon.”

As a result the passengers – mostly Americans, but also some French, Mexicans, Spaniards, English, Canadians and Irish – would be stuck in Horta for two weeks. Incidentally, it must be remembered that when waves at Horta’s maritime airport reached a height of one meter [39.37 inches], hydroplane take-offs became impossible. That’s why the aforementioned clippers were stranded in its bay.

Far from family and friends on the other side of the Atlantic, these involuntary visitors spent Christmas and New Year’s in Horta, giving great animosity to the city and mixing with the elite members of the Sociedade Amor da Pátria fraternal lodge. They were welcomed by the local circle of high society – namely Dr. Alberto Campos, president of the aforementioned society, and Dr. Humberto Santos Freitas, president of Sporting da Horta, among others – and left in writing a living testimonial about the kindness, friendliness and hospitality of the people of Faial.

As one way to fill their days of forced leisure, some of these foreigners decided to create a small newspaper, which they named The Horta Swell, written by them in English and illustrated with wood and linoleum block prints. Note that the English word “swell” as a noun means “undulation,” and as an adjective “great” – thus this double meaning evident in the newspaper’s title: the undulation of the sea did not let them go, but forced them to stay on Faial, and they recognized the outstanding welcome they received (“swell hospitality”). Between December 30, 1939, and January 7, 1940, six issues of The Horta Swell were published, produced in the print shop of O Telégrafo. Their short articles clearly reveal the state of mind of its authors who, “imprisoned” in Horta, dreamed of New York. The themes are described in a jolly and humorous tone in a writing style full of satire and upbeat irony. In prose and verse, passengers wrote letters and recorded the social chronicle of their Horta days: they wrote about local people and events, amused themselves with faits divers [anecdotes], news accounts of their circumstances and other notes about their status as “exiles,” entertained themselves by working crossword puzzles and adapting lyrics to popular American songs, composed poems and riddles, and praised Faial’s linguiça sausage and Pico’s verdelho wine (“swell Pico White”).

On January 5, 1940, the illustrious passengers finally left the Blue Island of Faial. To commemorate this event, a group of Faialense friends created a type of brotherhood, which they called “Horta Swell,” that annually gathered every January 5 to celebrate with a hearty dinner the departure of the clipper passengers. It was a “private organization of gastronomic purpose” based in two taverns, those of António Faria Jorge and António Lucas. The invitation was published in O Telégrafo and had only one item on the agenda: “It is already clear…” Members who were most distinguished in the Pantagruelian arts or the exploits of Bacchus were crowned throughout the year. Gatherings of these dining friends took place without interruption until the end of the 1960s. The Faial historian Carlos Ramos Silveira, a former employee of the submarine cable company Western Union Telegraph and a former bank employee, has written an interesting book on this subject that is strongly recommended here, The Horta Swell: uma história por contar [The Horta Swell: A Story to Tell] (Horta: self-published, 1995).

In his poem “Horta, quase requiem” [Horta, a Quasi Requiem], Pedro da Silveira referred to the Horta of that time: “And this was the anchored face of civilization! It was the happiest, biggest little city in the world.” Long live the city of Horta!

Portuguese-language original version published in The Portuguese Tribune, 15 August 2020, p. 26. And at www.portuguesetribune.com/articles/the-horta-swell