Translator’s Note to Adelaide Freitas’s

novel Smiling in the Darkness

By Katharine F. Baker, lead translator

"Call

me Isabel"

me Isabel"

Had

she wished, Adelaide Freitas could have opened her novel Smiling in the

Darkness with this sentence in English, because as a scholar of Herman

Melville’s epic Moby-Dick she knew the famous line "Call me Ishmael"

that opens its first chapter.

she wished, Adelaide Freitas could have opened her novel Smiling in the

Darkness with this sentence in English, because as a scholar of Herman

Melville’s epic Moby-Dick she knew the famous line "Call me Ishmael"

that opens its first chapter.

And

just as Melville’s mysterious survivor Ishmael relates his account of Captain

Ahab’s obsessive pursuit of the whale that had severed his leg, so too Isabel

narrates Smiling in the Darkness about her mother’s struggles to avenge

the amputation by her own father of her dreams and of the only family lifestyle

she’d known.

just as Melville’s mysterious survivor Ishmael relates his account of Captain

Ahab’s obsessive pursuit of the whale that had severed his leg, so too Isabel

narrates Smiling in the Darkness about her mother’s struggles to avenge

the amputation by her own father of her dreams and of the only family lifestyle

she’d known.

Notably,

both narrators’ names share most of the same letters – I-S-A-E-L – and in the

same order. Further, in Smiling in the Darkness, Isabel’s aptly-named

emigrant grandfather Fontes was the font of his family’s tribulations for

decades to come, starting in the 1920s after a visit to his native Azores to

find a bride to marry and take back to Massachusetts.

both narrators’ names share most of the same letters – I-S-A-E-L – and in the

same order. Further, in Smiling in the Darkness, Isabel’s aptly-named

emigrant grandfather Fontes was the font of his family’s tribulations for

decades to come, starting in the 1920s after a visit to his native Azores to

find a bride to marry and take back to Massachusetts.

As a

self-made man, Manuel Fontes prospered and advanced in New Bedford, while his uneducated wife kept

their home, bore his children, and turned a blind eye to his adulteries in

return for an increasingly wealthy life and the respectability of their

marriage’s false façade.

self-made man, Manuel Fontes prospered and advanced in New Bedford, while his uneducated wife kept

their home, bore his children, and turned a blind eye to his adulteries in

return for an increasingly wealthy life and the respectability of their

marriage’s false façade.

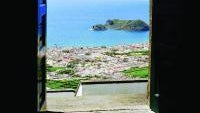

Then

disaster struck when one of Fontes’ mistresses insisted he evict his wife and

children from his mansion, and install her there; his family returned to their

native village on northeastern São Miguel.

This parallels Hagar and Ishmael’s being expelled by Abraham except that,

unlike in the Bible, exile was to the middle of an ocean rather than a desert.

Over the decades this expulsion precipitated one family member’s career-ending

literal near-amputation as well as a succession of emotional ones – Freitas

even had Isabel use the term "amputate."

disaster struck when one of Fontes’ mistresses insisted he evict his wife and

children from his mansion, and install her there; his family returned to their

native village on northeastern São Miguel.

This parallels Hagar and Ishmael’s being expelled by Abraham except that,

unlike in the Bible, exile was to the middle of an ocean rather than a desert.

Over the decades this expulsion precipitated one family member’s career-ending

literal near-amputation as well as a succession of emotional ones – Freitas

even had Isabel use the term "amputate."

However,

unlike the whale’s victim, the wounded Mrs. Fontes was no obsessed Captain

Ahab. Although illiterate, she had learned of a wider modern world, progress

and humanism in America,

where women enjoyed greater legal and cultural rights than in Portugal.

unlike the whale’s victim, the wounded Mrs. Fontes was no obsessed Captain

Ahab. Although illiterate, she had learned of a wider modern world, progress

and humanism in America,

where women enjoyed greater legal and cultural rights than in Portugal.

Thus,

upon returning home she would lead a more independent life than the village

women who had never left, she would think more rationally and less superstitiously

about natural and physical phenomena (including frequent major seismic

activity), and behave more pragmatically in relation to societal rules.

She

went unchaperoned about town and occasionally to the island’s main city,

refused to wear the widow’s weeds expected of divorcées, capably husbanded her

own money, refused to be cowed as others were by authority figures like the

schoolmaster or village priest, and dared to teach her grandchildren that God

lies within each person – a deity of tolerance and joy, not hellfire and

damnation.

upon returning home she would lead a more independent life than the village

women who had never left, she would think more rationally and less superstitiously

about natural and physical phenomena (including frequent major seismic

activity), and behave more pragmatically in relation to societal rules.

She

went unchaperoned about town and occasionally to the island’s main city,

refused to wear the widow’s weeds expected of divorcées, capably husbanded her

own money, refused to be cowed as others were by authority figures like the

schoolmaster or village priest, and dared to teach her grandchildren that God

lies within each person – a deity of tolerance and joy, not hellfire and

damnation.

It

was instead her daughter who – upon being suddenly stripped of her dreams of

studying to become a teacher, of having her own piano, pursuing her various

artistic inclinations, and generally living the wealthy lifestyle she’d known

in New Bedford – most keenly felt the consequences of the figurative

amputation, becoming as obsessed with her lost money and materialism as Ahab

had been with the whale that took his leg.

was instead her daughter who – upon being suddenly stripped of her dreams of

studying to become a teacher, of having her own piano, pursuing her various

artistic inclinations, and generally living the wealthy lifestyle she’d known

in New Bedford – most keenly felt the consequences of the figurative

amputation, becoming as obsessed with her lost money and materialism as Ahab

had been with the whale that took his leg.

After

marrying a local man and giving birth to five daughters (one of whom, the frail

tot Serafina, soon joined the seraphs) and a son, she found herself pregnant

again late in life, suffering complications and illness that necessitated

medical treatment as well as money to pay for it.

marrying a local man and giving birth to five daughters (one of whom, the frail

tot Serafina, soon joined the seraphs) and a son, she found herself pregnant

again late in life, suffering complications and illness that necessitated

medical treatment as well as money to pay for it.

However,

in a society still largely based on subsistence agriculture, hunting and

fishing, cash was scarce, so following daughter Xana’s difficult birth in late

October 1949 – only days after an airliner had slammed into massive nearby Pico

da Vara, killing all on board – and post-partum complications, the following

April ("the cruellest month") she decided to return to her native America long

enough to earn sufficient money from factory work to put her family on sounder

financial footing, leaving her children’s upbringing to their Papá and

both grandmothers.

in a society still largely based on subsistence agriculture, hunting and

fishing, cash was scarce, so following daughter Xana’s difficult birth in late

October 1949 – only days after an airliner had slammed into massive nearby Pico

da Vara, killing all on board – and post-partum complications, the following

April ("the cruellest month") she decided to return to her native America long

enough to earn sufficient money from factory work to put her family on sounder

financial footing, leaving her children’s upbringing to their Papá and

both grandmothers.

However,

six months later her husband joined her in New England to earn even more money

for the family – and over the years she would successively force their two

eldest daughters to come work in American factories upon completing their basic

schooling on São Miguel (while their only son came to find a job for himself,

and obtain a visa card for his fiancée, since employment opportunities for both

in Azores had worsened).

six months later her husband joined her in New England to earn even more money

for the family – and over the years she would successively force their two

eldest daughters to come work in American factories upon completing their basic

schooling on São Miguel (while their only son came to find a job for himself,

and obtain a visa card for his fiancée, since employment opportunities for both

in Azores had worsened).

The

three youngest daughters were raised by their grandmothers, especially their

maternal Vovó. Many years passed before their parents felt financially

able to return home, Mamã believing she had at last vanquished her whale

of money and materialism.

three youngest daughters were raised by their grandmothers, especially their

maternal Vovó. Many years passed before their parents felt financially

able to return home, Mamã believing she had at last vanquished her whale

of money and materialism.

But

while still in America she’d

begun planning grandiose renovations to their house in the Azores, and aspired

to a status comparable to the birthright she’d long ago enjoyed in Massachusetts. She

insisted on outdoing any neighbor’s challenge to her economic supremacy; she

wanted her family to be the Joneses with whom no other villager could keep up,

let alone surpass, an obsession leading inevitably to further familial

"amputations."

while still in America she’d

begun planning grandiose renovations to their house in the Azores, and aspired

to a status comparable to the birthright she’d long ago enjoyed in Massachusetts. She

insisted on outdoing any neighbor’s challenge to her economic supremacy; she

wanted her family to be the Joneses with whom no other villager could keep up,

let alone surpass, an obsession leading inevitably to further familial

"amputations."

Like Moby-Dick‘s

Ishmael, the cipher Isabel lived to tell the tale. However, by her allusion in

English on the first page of the original Portuguese edition of Smiling in

the Darkness to the opening line "April is the cruellest month" from T.S.

Eliot’s classic poem "The Wasteland," Isabel signaled that she had survived to

become erudite, even if the other relatives lived in a familial and cultural

wasteland, damaged by the latest amputation for at least another generation.

Ishmael, the cipher Isabel lived to tell the tale. However, by her allusion in

English on the first page of the original Portuguese edition of Smiling in

the Darkness to the opening line "April is the cruellest month" from T.S.

Eliot’s classic poem "The Wasteland," Isabel signaled that she had survived to

become erudite, even if the other relatives lived in a familial and cultural

wasteland, damaged by the latest amputation for at least another generation.

Originally published by The Portuguese Tribune

KATHARINE F. BAKER’s translations include I No Longer Like Chocolates by Álamo Oliveira, The Portuguese Presence in California by Eduardo Mayone Dias, and My Californian Friends: Poetry by Vasco Pereira da Costa.